A final word about conjugating regular ER verbs in the present tense.

Remember this post about modal verbs and the boot? ER verbs are not boot verbs, but I often think of them that way because everything inside the boot is pronounced the same way.

Yes, even the ils/elles conjugation. Never pronounce the "-ent" ending in a conjugated verb. The "-ent" might affect how the letters before it are pronounced, but the "-ent" itself is never pronounced.

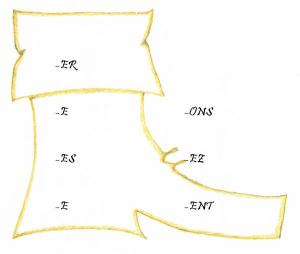

Je parle Nous parlons

Tu parles Vous parlez

Elle parle Ils parlent

Yes, that's right. "Parle", "parles", and "parlent" are all pronounced exactly the same way. Fight the urge to say "parl-ant." You can beat this – I know you can.

That said, not every "-ent" is silent. Only the "-ent" ending of a conjugated verb. If the "ent" is part of the stem (or "radical") of the verb, or if you find "-ent" at the end of a word that is not a verb – it's fair game. Go ahead and pronounce that sucker. (For example: un accident, un élément, un tempérament.)

And I'm sorry, but just like in the Lord of the Rings, there are no Entwives here. Only -ents.