This piece is the right shape, but the wrong design. This piece is the right design, but the wrong shape. This piece should fit, but it doesn’t and that piece shouldn’t, but apparently it does. I’ve always loved jigsaw puzzles – the more challenging the better. In fact I’m crazy enough to think of 2,000 pieces as the minimum size for a puzzle.

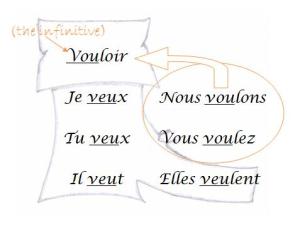

All of this really has nothing to do with verb conjugation, except that sometimes I think of conjugating verbs like working a puzzle. First you take your infinitive (part of the picture on the puzzle box) and then you take the stem (one puzzle piece) and finally you find the right ending (another puzzle piece), put them together and you have your verb – part of your sentence (your completed puzzle). A little sad maybe, but anything that makes verb conjugation less painful is a good thing.

Lost? Okay, we’re going back to the basics:

I cake.

You cakes.

We with each other.

Does something seem to be missing from those “sentences”? How’s this:

I love cake.

You bake cakes.

We belong with each other.

Aww… but maybe that was:

I love cake.

You hate cakes.

We fight with each other.

Huh.

Lesson #1: Verbs are important!

Okay, and then there’s:

I loves cake.

You baking cakes.

We to belong together.

Lesson #2: How you form the verb matters!

Lesson #2 is a perfect example of what happens when you don’t know how to conjugate a verb. Verb conjugation is simply the act of forming the verb correctly based on the subject (who’s doing the action) and the format of the rest of the sentence. It’s tempting for students of a foreign language to think that as long as they know the verb and what it means, that’s enough, but really, do you want to walk around in French saying “you baking cakes” when you mean “you bake cakes”?

I didn’t think so. So, you start with your infinitive (the unconjugated verb). For example:

parler to talk

Take the stem (the beginning) of the verb and separate it from the ending. How do you know where to break the verb? Some of it will just come down to memorization and comfort with the language, but there are five core categories of verbs in French and they are defined largely by their endings.

-ER verbs

-IR verbs

-RE verbs

-Stem changing verbs

-Irregular verbs

- ER verbs are by far the most common regular French verbs and they all end with, you guessed it, -ER. So, in our example, “parl-” would be your stem and “-er” would be your ending.

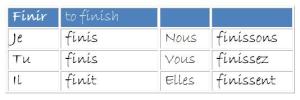

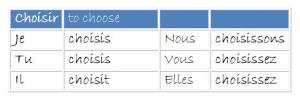

- IR verbs are the second most common regular French verbs and, shockingly, they all end with –IR. (Finir – stem = fin, ending = ir.)

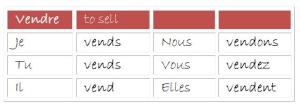

- RE verbs… I think you know where I’m going with this. (Rendre – stem = rend, ending = re.)

- Stem changing verbs – usually it is the ending that changes and the stem that stays the same, but some verbs are just a little trickier and to conjugate them you have to change both the stem and the ending. These verbs are particularly difficult for beginners because only the infinitive shows up in the dictionary. So if you stumble across an unfamiliar stem-changing verb and want to look it up… it might be a little tricky. (Essayer – “j’essaie” and “nous essayons.”

- Irregular verbs – A lovely category meaning “everything else.” Okay, so technically it means all the verbs that don’t follow one easily memorized pattern. Irregular verbs have to be memorized individually or in small groups.

Then you choose your subject or subject pronoun. In French the subject pronouns are:

(The brackets show subjects that share the same conjugation. You’ll notice that when I’m writing out the full conjugation of a verb, I often write only “il” or “elle” and “ils” or “elles”. The rule still applies to the missing pronouns; I just leave them out for simplicity.)

(The brackets show subjects that share the same conjugation. You’ll notice that when I’m writing out the full conjugation of a verb, I often write only “il” or “elle” and “ils” or “elles”. The rule still applies to the missing pronouns; I just leave them out for simplicity.)

So, now you have your verb stem (parl) and your subject pronoun – now you, um…, conjugate the verb. You take the stem and you add the appropriate ending, depending on what your subject is.

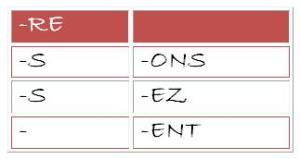

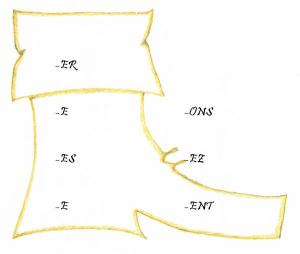

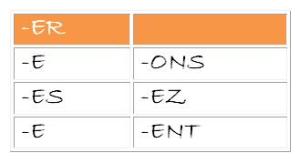

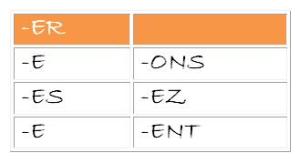

It might help if you had some rules, so we’re just going to dive into the ER verbs in the present tense. There is one pattern, one rule, for conjugating all regular –ER verbs and remember, once you know it, you know how to conjugate the largest group of French verbs! Here goes:

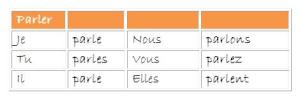

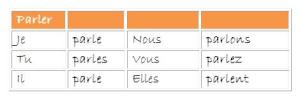

Simple, right? Every single regular ER verb follows that pattern. Our example was “parler” and here’s how it looks conjugated in the present tense:

Okay, now it’s your turn. Try with the verb “aimer” “to love”. Answers below, (highlight to see them – but don’t cheat! Try it yourself first!)

J’aime Nous aimons

Tu aimes Vous aimez

Elle aime Ils aiment

Congratulations! You’re on your way to being a verb-conjugating fiend!

Attendre – does not mean “to attend.” Don’t even think it. Also, note that in English you wait “for” someone, but you do not add “pour” to the corresponding French phrase. “J’attends mon ami.”

Attendre – does not mean “to attend.” Don’t even think it. Also, note that in English you wait “for” someone, but you do not add “pour” to the corresponding French phrase. “J’attends mon ami.”